The myriad throng: Human effective population size

Economy recapitulates demography? (image source) Iranians count their rials in superunits of the toman, from a Mongol word for ten thousand soldiers. Remarkably, such a modest-sized horde could readily harbor much of the genetic diversity that long characterized people worldwide. But, with prices rising in Iran, a toman can reportedly now mean ten million rials. And a new genetic census of humanity hints, likewise, at rampant inflation in our ranks…

Several weeks ago, we reviewed how a newly documented trove of rare variants in human genomes tracks our ballooning population. Most such variants, we saw, arose by recent mutations near the tips of our family tree — and now, like yuletide lights, mark out the tree’s fast-sprouting outer branches. The lengths of those branches, in turn, reflect a great proliferation of human ancestors as our population has exploded during the past few millenia.

But despite the rare variants that track our recent population growth, human genomes are still strikingly alike. Geneticists have long known, in particular, that two randomly chosen copies of a typical human chromosome tend to differ in spelling at less than one in a thousand letters.

Given what’s known about how fast DNA mutates, this is remarkably little variation. So little, in fact, that, despite our teeming numbers, the stock of variation in our genomes is, at first glance, roughly what we’d expect to find in a steady-sized population of just ten thousand randomly mating individuals.

So what gives? How can our genomes suggest a population that’s bursting the planet’s seams, yet small enough to gather in Wimbledon Centre Court?

Below we’ll learn how to guess directly at a population’s size from the profile of genetic variation that it carries, retracing how geneticists originally arrived at the ten thousand figure. And we’ll see how more nuanced math is revising our genetic census to better reflect the explosive growth that has loaded today’s billions of real human genomes with so many rare new variants.

Consider a spherical gene pool…

Geneticists use the term effective population size to mean the number of idealized individuals who would typically harbor the same genetic diversity seen in a set of real organisms (whom the idealized ones ‘effectively’ represent). In shorthand, this size is denoted Nₑ, where N stands for ‘number’ and e stands for, well, ‘effective’.[1]

Ultimately, the concept of Nₑ is the kind of simplification that a physicist might make in predicting the arc of a cow launched from a circus cannon. Bear with me on this, ok?

A cow is a complex lump of stuff, and modeling its flight precisely, down to the last whisker, would take great knowledge and computing power. But, where reasonable, scientists like to lazily simplify things. So, rather than try to account for every cranny of the cow’s shape, every quirk of density and electric charge inside it, and every component of its motion (methane release-induced yaw…), a physicist might model the cow as a chargeless point mass flying in a vacuum.

Because such an idealized mass would fly in a simple path, immune to aerodynamic, electrostatic, buoyant (were this an underwater flight) or other such real-cow effects, it might be, say, a bit lighter than the real cow and still fly just as far. A physicist might think of that smaller mass as the ‘effective mass’ of the cow.

Or, more realistically, our physicist might accept that cows fly through real air (or water), and have nonzero volume, and so model the cow (still simplistically, of course) as a symmetrical ball with the cow’s mass and net density. To the extent that the flight of such a ball approximated that of the real cow, the ball’s radius could be called the ‘effective radius’ of the cow.

Geneticists can model the evolutionary trajectories of populations, on likewise simplistic lines. Rather than try to track (or guess precisely at) every detail of mating, fertility, migration, and mutation in a population’s history, they often make simple assumptions about those processes. And those assumptions, to the extent valid, can point to an ‘effective size’ that gives a rough handle on how a given population is evolving.

Happy little trees

The link between population size and genetic variation can be seen most clearly through the lens of genealogical tree shape, as introduced here.

To put hard numbers on that connection, let’s sketch the family tree of all copies of just one site in the genomes of a population. Taking a cue from the great Bob Ross, we’ll paint our tree in simple strokes: it will represent a population of some big, constant number N individuals, who breed at most once, in discrete generations, blindly with respect to their genotypes, without complications from factors like natural selection, geography, or recombination.[2]

If these N idealized individuals have simple two-copy genomes like our own, then each site in those genomes has 2_N_ total copies in the population overall. The family tree for a given site then represents the ancestries of all 2_N_ copies as a skeletal graph, tracing how they’ve been copied from one generation to the next.

Now, here’s a crucial point about our model: we’ll stipulate that, looking back in time, toward the root of the tree, each copy of the site in a given generation traces back at random to one of the 2_N_ copies in the generation before — and does so regardless of whether any other copy also traces back to that same previous-generation copy.

This means that, while there are always 2_N_ copies of the site in the model population, only some of them, in any given generation, are copied into the next one. That is, a given copy today may give rise to more than one of tomorrow’s 2_N_ copies — while other copies, by chance, end up as evolutionary dead ends.[3]

And that sheer randomness is, ironically, where the math gets precisely predictive.

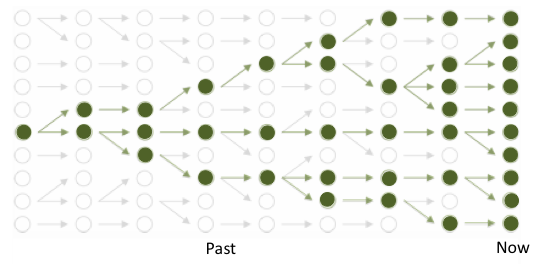

Tree (bold green) tracing the ancestry of a population of ten modern copies of a genomic site, amid branches of overall genealogy (gray) of constant-sized population. Arrows point forward in time, linking one generation to the next; coalescences are found by tracing lineages backward (toward left) til they meet. (figure adapted from lectures by Gil McVean)

Chance encounters

Notice, in particular, that our simple model gives any two copies of the site in a given generation a one-in-2_N_ chance of tracing back to the same parent copy in the previous generation.

Because N is big, that chance is tiny. But (but!…) if we look back over enough generations, the lineages of those two copies will eventually meet at some shared ancestor. That is, chance dictates that they won’t forever keep tracing to separate ancestral copies, but at some point will happen to trace to the same one.

Such random lineage mergers — which geneticists call coalescences — are, in the end, why the family tree of the 2N copies is indeed a tree, rather than just a bundle of 2_N_ endless, unconnected vines.

And, while the math in question looks hairy at first, it works out that, for big N under our simplistic assumptions, the mean number of generations that it takes two copies’ lines to meet (looking back in time) approaches 2_N_. That is, the average time back to a merger becomes the reciprocal of the one-in-2_N_ chance of a merger in any single generation.

A neat, simple result.

Of course, if you use a computer to simulate the ancestries of many paired copies of the site under our model, you’ll find that the actual number of generations since coalescence varies randomly — a lot — around this average. But the average itself is nonetheless very handy.

Mutations: buds on the branches

In particular, knowing the average time separating two randomly chosen copies of a site means that, if we also know how often a typical copy mutates (randomly changes in DNA spelling), we can estimate how many mutations will most typically have happened along the two branches that, meandering back through time, ultimately unite the pair of copies.

Let’s use the letter μ for that per-generation, per-copy chance of mutation at the site. And we’ll note that, because each of the two branches that separate the paired copies of the site is, on average, 2_N_ or so generational copyings long, they tend to be separated by roughly 4_N_ generation-lengths overall.

With these simple observations, we can estimate the number of mutations that separate the two copies of the site as [drumroll…] 4_Nμ_.

Importantly, this number closely approximates the cornerstone measure of sequence variation in a population, nucleotide diversity, which we encountered here.[4]

And this result — that nucleotide diversity should be roughly 4_Nμ_ in our simple model population — is the basic nugget of insight that ties the historical size of a population directly to the pattern of genetic variation that it carries. That is, if we know two of the variables in question — nucleotide diversity and μ — we can in principle estimate the third variable, the size N of the population.

But recall that our simple model presumes the population to be steady-sized, with no natural selection, and so forth — conditions that don’t strictly hold in the real world. As such, like physicists modeling a flying cow, we’re actually using this simple 4_Nμ_ insight to estimate the population’s effective size, Nₑ.

The few, the proud, the effective.

So what, in the end, are the values of the two measurable variables, nucleotide diversity and μ, that suggest how many human genomes are — effectively — out there?

Depending on whom you look at, human nucleotide diversity ranges from roughly 0.0007 (for people who descend mainly from the fairly few ancient inhabitants of the Americas) to 0.001 (for people with recent ancestry in Africa, where we’ve been densely settled the longest, letting the most genetic diversity, per capita, arise and persist). That is, copies of human chromosomes tend to differ from each other at roughly seven to ten letters out of every ten thousand.

And many studies of human and other DNA suggest that μ is roughly 1 to 3.5 x 108 per generation. That is, the genome of a viable human egg or sperm typically acquires a new spelling at roughly one letter per thirty to a hundred million.[5]

Putting these numbers together yields an estimate of human Nₑ at roughly ten (versus one or a hundred) thousand. Note that this is a back-of-the-envelope, order-of-magnitude kind of guess, and that it varies by what regional slice of humanity we look at (reflecting, in the end, real spatial variation in the longterm density of human settlement). More importantly, it clearly underestimates our real population size of roughly seven billion.[6]

And that difference is telling. Effective population size for any organism is typically less than the census size (and need not ever equal it), of course — that’s why it’s called ‘effective’, rather than ‘real’. But the fact that human Nₑ per se looks so low has long been a clue that our real population itself was long much smaller than it is now.[7] The newly documented glut of rare variants in our genomes strongly undergirds this idea, suggesting that very recently (in evolutionary terms) our population has grown much, much bigger.

As such, the overall data on human genetic variation clearly break the assumption of constant population size on which we simplistically estimated Nₑ in our simple model. But that estimate is stubbornly low for other reasons too.

Post-diluvian tree. Bald cypress with flood line, Carbondale, IL. (image copyright Nathaniel Pearson)

Caution: Populations are bigger than they appear

First, the trees generated by our model are, technically, most accurate for samples much smaller than the sampled population. As we look at more and more individuals, the model will tend to slightly underestimate the lengths of the tree’s outermost branches — an effect that may contribute a (tiny) smidgen to the dilation of branches inferred in recent papers on the many rare variants found in samples comprising many thousands of people.

Second, and more importantly, most of the other hidden ways in which real populations can buck our über-simple model (besides change in size) tend to make them look even smaller. For example, a population comprising partly isolated sub-populations of various sizes, or one that undergoes the most common kind of natural selection, tends to look, in genetic terms, even smaller than we’d otherwise expect.[8]

Third, it turns out that, even if we realistically refine our simple model to let population size vary, the best longterm estimate of Nₑ roughly tracks the harmonic mean of the population size over time — which in turn hews closely to the smallest value that the population passes through.

Thus, while our genomes do bear telltale signs of recent population growth, they also inevitably retain strong imprints of earlier eras when our ancestors were far fewer. Genetic diversity tends to be very sensitive to the demographic squeeze of a so-called population bottleneck — and it’s thought that our ancestors likely underwent one or, pending where they lived, even several severe ones.

Grafting trees

To better detect such a mix of population-size signals, geneticists can readily extend the basic coalescent model by dividing a genetic family tree into two or more parts, and modeling each in relative isolation.

They might, for example, single out one set of branches from the rest, to reflect the geographic isolation of some lineages from others (perhaps compounded by regional differences in sub-population size, natural selection, and so forth).

Or, more to our point, they could simply mark a height across the whole tree — like a flood mark on a mangrove or cypress — to specify a moment in the past when the size (or other evolutionary attributes) of the whole ancestral population changed.

In any such case, we get a tree that looks like multiple trees grafted together, as if by Dr. Frankenstein, to more realistically resemble the true genealogy of real copies of the genomic site in question.

If, for example, a population started growing at a marked time point, the resulting tree might have fairly stunted inner branches root-ward of that point, and longer outer branches leaf-ward of it. Conversely, if the population started shrinking at the chosen moment, the line drawn at the point in question would divide relatively stunted outer branches from longer inner ones.

Like master gardeners sculpting bonsai to the form of a wild tree, geneticists can tune their demographic assumptions — how big a population was originally, when and how fast it grew or shrank, etc. — to best fit their model trees to the real ancestral tree of copies of a genomic site.[9] As we’ve seen, the shape of that underlying genealogy is roughly discernible by measuring mutational differences among those copies, to proxy the lengths of the various ancestral branches that unite them.

Promisingly, the new papers on human rare variant burden use such tuning to re-estimate our effective population size to be on the order of millions, rather than mere thousands. Tennessen et al., for example, estimate the modern effective population sizes of Africans and Europeans to both be roughly half a million each; and Keinan and Clark estimate that European Nₑ is now roughly 1.1 million. Note that, in such estimates, exact numbers matter less than orders of magnitude. Models with so many parameters are easy to overfit — and human population history is obviously complex, defying any attempt to distill real demography to a simple trend in effective population size — so we shouldn’t demand especially precise inferences.

The wheel’s still in spin

Most importantly, the new papers make clear that the human population has likely grown even more quickly than exponentially in the past few millenia. Recalling our bovine ballistics analogy, we could liken such growth to a flying cow sprouting strikingly long, skinny legs.

Those legs weigh (and impede the wind) less than the bulk of its body, leaving the cow’s effective mass or radius somewhat smaller than we might expect, given the gangly havoc it would wreak in a china shop. But just as a calf’s growth spurt eventually leaves it much heavier, the recent population explosion that sowed our bumper crop of rare genetic variants may, in the long run, boost our effective population size tremendously.

That is, if we stably inhabit earth (or beyond) at or above our current density for a long time, many of our currently rare variants will, by chance or otherwise, become modestly common enough to distinguish many chromosomal copies from each other, pushing our nucleotide diversity well above today’s humble figures.[10] Our effective population size, as measured by overall diversity in our genomes, should then continue to shift toward a new, if elusive, equilibrium that more closely tracks our teeming numbers.

Along the way, our changing population size may shape public health in complex ways. In particular, a key question will be what happens to the likely sizable subset of newly arisen rare variants that pose health risks to people who carry them. As our population continues to skyrocket, more such variants will come into our midst.

At the same time, continued population growth should ultimately help natural selection purge such variants more efficiently than it can in a small population (where chance dominates the fate of variants, harmful or not).

But, to the extent that our future population growth itself depends on further advances in healthcare, we’ll also be altering the regime of such natural selection, ideally relaxing it in ways that help people live healthier lives no matter what variants they carry in their genomes.

If we can manage that, of course, we’ll have become an effective population in a deeper, more important sense yet.

[^1] Except under special conditions, Nₑ will be met or, more commonly, exceeded by the size of the real population.

[^2] On the breed-at-most-once criterion, note that we’ll let them have more than one child per breeding episode — an important point, as we’ll see. Note too that we ignore some subtleties of mating itself, focusing more on ancestral chains of copyings of a genomic site than on the kinship of the individuals who carry those copies. The latter turns out to matter fairly little overall.

[^3] Note that a given copy in one generation can end up as a dead end even if it is copied down into the next generation, if its lineage doesn’t make it into the last (i.e., current) generation. Thus the heartwarming truism that you, and everyone you know, descend only from winners in the evolutionary game. In coalescent models, dead-end branches that don’t reach the current generation are typically ignored, simplifying the tree to just the skeleton that ties together all current copies of the site (which you can picture as the tree’s leaves).

[^4] This holds if mutation is consistently very rare — and it generally is — so that the branches connecting the two copies of a site hardly ever harbor more than one mutation overall.

[^5] A sperm tends to carry more new mutations than an egg does, however, in part because the average sperm derives from many more mutation-prone cell divisions in the body than the average egg does.

[^6] Coincidentally, there are now roughly as many living people as letters in a human genome, if we include the repetitive and tightly bound up genome segments that are especially hard to read.

[^7] Natural selection, non-random mating, and other factors inevitably also play roles in that deviation, in ways that we’re still figuring out. Much research today aims to understand human evolution in fine strokes, focusing on particular parts of the genome (which may differ in their histories, reflecting their roles in disease, adaptation to particular environments, and so forth) and particular populations (which have split and merged in complex patterns that we can, by carefully surveying shared versus distinctive patterns of genetic variation, start to deduce in some detail).

[^8] Notably, along these lines, the concept of effective population size itself conventionally presumes no natural selection at all. That is, the subscript e can effectively be read as ‘if there were no selection’. When geneticists do explicitly parametrize natural selection in relevant models, they typically drop the ‘effective’ from the population size term (while still acknowledging that the remaining term N is a rough estimate). Distinguishing the conventional, singularly definitive Nₑ from other abstractions of population size turns out to be tricky in other complex (read: realistic) evolutionary scenarios too, such as when a population is split into subpopulations, with sporadic migration among them.

[^9] Or, more often, a multi-site segment, which allows more precise measurement of differences among copies (though risks complication from recombination history).

[^10] Strikingly, coarse, nucleotide diversity-based estimates of our effective population size are lower not just than those of, say, fruitflies — but even those of most other great apes, suggesting that, despite our current global prominence, they’ve outnumbered us for much of our history.